1. JavaScript Concepts

- 1. JavaScript Concepts

1.1. Data types

The latest ECMAScript standard defines seven data types:

Six data types that are primitives:

- Boolean

- Null

- Undefined

- Number

- String

- Symbol (new in ECMAScript 6)

- and Object

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Data_structures

1.2. Prototypal inheritance

When it comes to inheritance, JavaScript only has one construct: objects.

Each object has a private property which holds a link to another object called its prototype. That prototype object has a prototype of its own, and so on until an object is reached with null as its prototype.

By definition, null has no prototype, and acts as the final link in this prototype chain.

When trying to access a property of an object, the property will not only be sought on the object but on the prototype of the object, the prototype of the prototype, and so on until either a property with a matching name is found or the end of the prototype chain is reached.

In JavaScript, any function can be added to an object in the form of a property. An inherited function acts just as any other property, including property shadowing as shown above (in this case, a form of method overriding).

When an inherited function is executed, the value of this points to the inheriting object, not to the prototype object where the function is an own property.

1.2.1. How prototypal inheritance works

All JavaScript objects have a prototype property, that is a reference to another object. When a property is accessed on an object and if the property is not found on that object, the JavaScript engine looks at the object's prototype, and the prototype's prototype and so on, until it finds the property defined on one of the prototypes or until it reaches the end of the prototype chain. This behavior simulates classical inheritance, but it is really more of delegation than inheritance.

When creating a new object/class, methods should normally be associated to the object's prototype rather than defined into the object constructor. The reason is that whenever the constructor is called, the methods would get reassigned (that is, for every object creation).

function MyObject(name, message) {

this.name = name.toString();

this.message = message.toString();

this.getName = function() {

return this.name;

};

this.getMessage = function() {

return this.message;

};

}

Because the previous code does not take advantage of the benefits of using closures in this particular instance, we could instead rewrite it to avoid using closure as follows

function MyObject(name, message) {

this.name = name.toString();

this.message = message.toString();

}

MyObject.prototype.getName = function() {

return this.name;

};

MyObject.prototype.getMessage = function() {

return this.message;

};

In the two previous examples, the inherited prototype can be shared by all objects and the method definitions need not occur at every object creation.

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Inheritance_and_the_prototype_chain

1.3. Scoping

JavaScript has two scopes – global and local. Any variable declared outside of a function belongs to the global scope, and is therefore accessible from anywhere in your code. Each function has its own scope, and any variable declared within that function is only accessible from that function and any nested functions.

Consider the following:

function foo(a) {

console.log( a + b );

}

var b = 2;

console.log(foo( 2 )); // 4

The reference for b cannot be resolved inside the function foo, but it can be resolved in the scope surrounding it (in this case, the global).

1.3.1. Lexical Scope

There are two predominant models for how scope works. The first of these is by far the most common, used by the vast majority of programming languages. It’s called lexical scope, and we will examine it in depth. The other model, which is still used by some languages (such as Bash scripting, some modes in Perl, etc) is called dynamic scope.

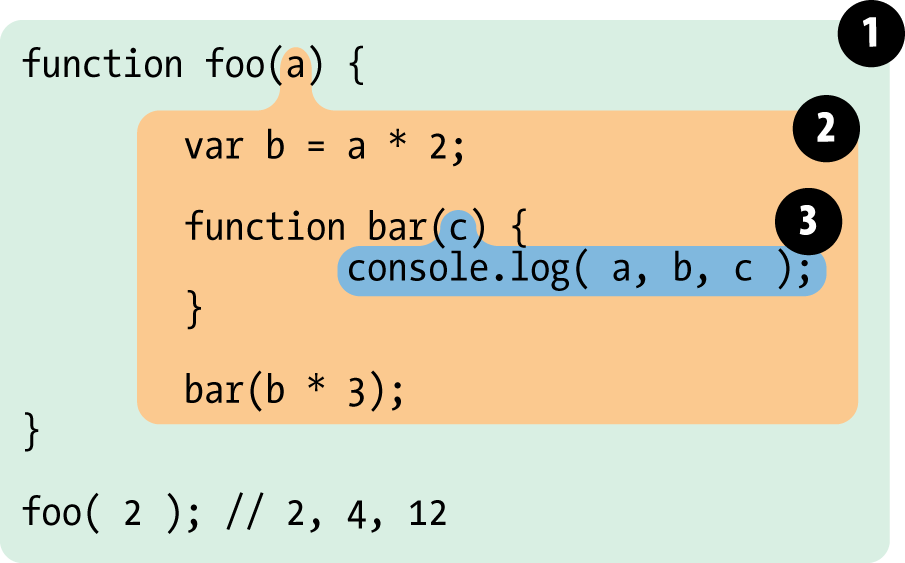

Let’s consider this block of code:

function foo(a) {

var b = a * 2;

function bar(c) {

console.log( a, b, c );

}

bar( b * 3 );

}

console.log(foo( 2 )); // 2, 4, 12

There are three nested scopes inherent in this code example. It may be helpful to think about these scopes as bubbles inside of each other.

- Bubble 1 encompasses the global scope and has just one identifier in it:

foo. - Bubble 2 encompasses the scope of

foo, which includes the three identifiers:a,bar, andb. - Bubble 3 encompasses the scope of

bar, and it includes just one identifier:c.

1.3.2. What is "this" Context

Context is most often determined by how a function is invoked. When a function is called as a method of an object, this is set to the object the method is called on:

var obj = {

foo: function() {

return this;

}

};

obj.foo() === obj; // true

1.4. Closures

A closure is an inner function that has access to the outer (enclosing) function's variables—scope chain.

A closure is the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared.

var a = 2;

(function foo(){

var a = 3;

console.log( a ); // 3

})();

console.log( a ); // 2

This pattern is so common, a few years ago the community agreed on a term for it: IIFE, which stands for immediately invoked function expression.

The following closure has three scope chains: it has access to its own scope (variables defined between its curly brackets), it has access to the outer function's variables, and it has access to the global variables.

var Module = (function() {

var privateProperty = 'foo';

function privateMethod(args) {

console.log('privateMethod', args);

}

return {

publicProperty: 'some value',

publicMethod: function(args) {

console.log('do something', args);

},

privilegedMethod: function(args) {

return privateMethod(args);

}

};

})();

console.log(Module);

Module.publicMethod();

1.4.1. What is a closure, and how/why would you use one?

A closure is the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared. The word "lexical" refers to the fact that lexical scoping uses the location where a variable is declared within the source code to determine where that variable is available. Closures are functions that have access to the outer (enclosing) function's variables—scope chain even after the outer function has returned.

Why would you use one?

- Data privacy / emulating private methods with closures. Commonly used in the module pattern.

- Partial applications or currying.

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Closures

1.4.2. The event loop

The event loop is a single-threaded loop that monitors the call stack and checks if there is any work to be done in the task queue. If the call stack is empty and there are callback functions in the task queue, a function is dequeued and pushed onto the call stack to be executed.

JavaScript has a concurrency model based on an "event loop". This model is quite different from models in other languages like C and Java.

The event loop got its name because of how it's usually implemented, which usually resembles:

while (queue.waitForMessage()) {

queue.processNextMessage();

}

queue.waitForMessage() waits synchronously for a message to arrive if there is none currently

Function calls form a stack of frames.

function foo(b) {

var a = 10;

return a + b + 11;

}

function bar(x) {

var y = 3;

return foo(x * y);

}

console.log(bar(7)); //returns 42

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/EventLoop

1.5. Events

Events are occurrences that take place in the interaction between the user, the web page, and the browser. Event handling enables a script to detect and react to these occurrences, allowing the web page to become interactive.

1.5.1. Event Handling

There are three steps to handling an event.

First, you need to locate the element that will receive the event. Events always take place in the context of element nodes inside the DOM tree.

<a href="http://www.google.com" id="mylink">My link</a>The next step is to create an event handler, which is the code that will execute when the event occurs.

function myEventHandler() { alert("Event triggered"); }Finally, the last step is to register the event handler for the particular event that is to be handled.

var mylink = document.getElementById("mylink"); mylink.onclick = myEventHandler;

1.5.2. Event Propagation

Most DOM events have event propagation, meaning that an event triggered on an inner element will also trigger for outer elements. To illustrate, here is a paragraph element nested inside a div element.

<div id="outer">Outer element

<p id="inner">Inner element</div>

</div>

The following code registers click events for both of these elements using the traditional model.

var inner = document.getElementById("inner");

inner.onclick = function() {

alert("Inner");

};

var outer = document.getElementById("outer");

outer.onclick = function() {

alert("Outer");

};

After an event triggers on the inner element, it then continues to trigger any event handlers attached to parents in nesting order. Therefore, clicking on the inner element will here display the “Inner” message first, followed by the “Outer” message. This default event order is called bubbling.

1.5.3. Event bubbling and capturing explained

When an event is fired on an element that has parent elements (e.g. the <video> in our case), modern browsers run two different phases — the capturing phase and the bubbling phase.

In the capturing phase:

- The browser checks to see if the element's outer-most ancestor (

<html>) has an onclick event handler registered on it in the capturing phase, and runs it if so. - Then it moves on to the next element inside

<html>and does the same thing, then the next one, and so on until it reaches the element that was actually clicked on.

In the bubbling phase, the exact opposite occurs:

- The browser checks to see if the element that was actually clicked on has an onclick event handler registered on it in the bubbling phase, and runs it if so.

- Then it moves on to the next immediate ancestor element and does the same thing, then the next one, and so on until it reaches the

<html>element.

1.6. Apply, call, and bind

These two methods inherent to all functions allow you to execute any function in any desired context. This makes for incredibly powerful capabilities.

- The

callfunction requires the arguments as a comma seperated list. - The

applyfunction requires the arguments as an array.

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

console.log(add.call(null, 1, 2)); // 3

console.log(add.apply(null, [1, 2])); // 3

An easy way to remember this is C for

calland comma-separated and A forapplyand an array of arguments.

The result of both calls is exactly the same, the add function is invoked in the context of the window and provided the same two arguments.

1.6.1. Explain Bind

ECMAScript 5 (ES5) introduced the Function.prototype.bind method that is used for manipulating context. It returns a new function which is permanently bound to the first argument of bind regardless of how the function is being used.

For example:

function Widget() {

this.element = document.createElement('div');

this.element.addEventListener('click', this.onClick.bind(this), false);

}

Widget.prototype.onClick = function(e) {

// do something

console.log('onClick', e);

};

1.7. Callbacks and promises

The Promise object represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation, and its resulting value.

A Promise is in one of these states:

pending: initial state, neither fulfilled nor rejected.fulfilled: meaning that the operation completed successfully.rejected: meaning that the operation failed.

var promise1 = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(resolve, 100, 'foo');

});

console.log(promise1);

1.7.1. What are the pros and cons of using Promises instead of callbacks?

Pros:

- Avoid callback hell which can be unreadable.

- Makes it easy to write sequential asynchronous code that is readable with .then().

- Makes it easy to write parallel asynchronous code with Promise.all().

Cons:

- Slightly more complex code (debatable).

- In older browsers where ES2015 is not supported, you need to load a polyfill in order to use it.

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Promise

1.8. Variable and function hoisting

Hoisting is JavaScript's default behavior of moving all declarations to the top of the current scope (to the top of the current script or the current function).

- In JavaScript, a variable can be declared after it has been used.

- In other words; a variable can be used before it has been declared.

Variables and constants declared with let or const are not hoisted!

myFunction();

function myFunction() {

y = 3.14; // This will also cause an error because y is not declared

}

Function declarations have the body hoisted while the function expressions (written in the form of variable declarations) only has the variable declaration hoisted.

"use strict";https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Strict_mode

One of the advantages of JavaScript putting function declarations into memory before it executes any code segment is that it allows you to use a function before you declare it in your code. For example:

function catName(name) {

console.log("My cat's name is " + name);

}

catName("Tigger");

/* The result of the code above is: "My cat's name is Tigger" */

The above code snippet is how you would expect to write the code for it to work. Now, let's see what happens when we call the function before we write it:

catName("Chloe");

function catName(name) {

console.log("My cat's name is " + name);

}

/* The result of the code above is: "My cat's name is Chloe" */

Even though we call the function in our code first, before the function is written, the code still works. This is because of how context execution works in JavaScript.

Hoisting works well with other data types and variables. The variables can be initialized and used before they are declared.

1.8.1. Only declarations are hoisted

JavaScript only hoists declarations, not initializations. If a variable is declared and initialized after using it, the value will be undefined.

For example:

console.log(num); // Returns undefined

var num;

num = 6;

If you declare the variable after it is used, but initialize it beforehand, it will return the value:

num = 6;

console.log(num); // returns 6

var num;

The below two examples demonstrate the same behavior.

var x = 1; // Initialize x

console.log(x + " " + y); // '1 undefined'

var y = 2; // Initialize y

// The above example is implicitly understood as this:

var x; // Declare x

var y; // Declare y

// End of the hoisting.

x = 1; // Initialize x

console.log(x + " " + y); // '1 undefined'

y = 2; // Initialize y

Function declarations have the body hoisted while the function expressions (written in the form of variable declarations) only has the variable declaration hoisted.

1.8.2. Function Declaration

console.log(foo); // [Function: foo]

foo(); // 'FOOOOO'

function foo() {

console.log('FOOOOO');

}

console.log(foo); // [Function: foo]

1.8.3. Function Expression

console.log(bar); // undefined

bar(); // Uncaught TypeError: bar is not a function

var bar = function() {

console.log('BARRRR');

};

console.log(bar); // [Function: bar]

Reference: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Hoisting

1.9. Currying

Currying is a pattern where a function with more than one parameter is broken into multiple functions that, when called in series, will accumulate all of the required parameters one at a time.

This technique can be useful for making code written in a functional style easier to read and compose. It's important to note that for a function to be curried, it needs to start out as one function, then broken out into a sequence of functions that each accepts one parameter.

function curry(fn) {

if (fn.length === 0)

return fn;

function _curried(depth, args) {

return function(newArgument) {

if (depth - 1 === 0)

return fn(...args, newArgument);

return _curried(depth - 1, [...args, newArgument]);

};

}

return _curried(fn.length, []);

}

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

var curriedAdd = curry(add);

var addFive = curriedAdd(5);

var result = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5].map(addFive); // [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

console.log(result);

Reference: https://www.sitepoint.com/currying-in-functional-javascript/